‘AK Indigenous Educators Present Research at University of Helsinki’ by Anya Nelson and Luke Fortier

- Our Alaskan Schools Blog

- Jul 26, 2024

- 5 min read

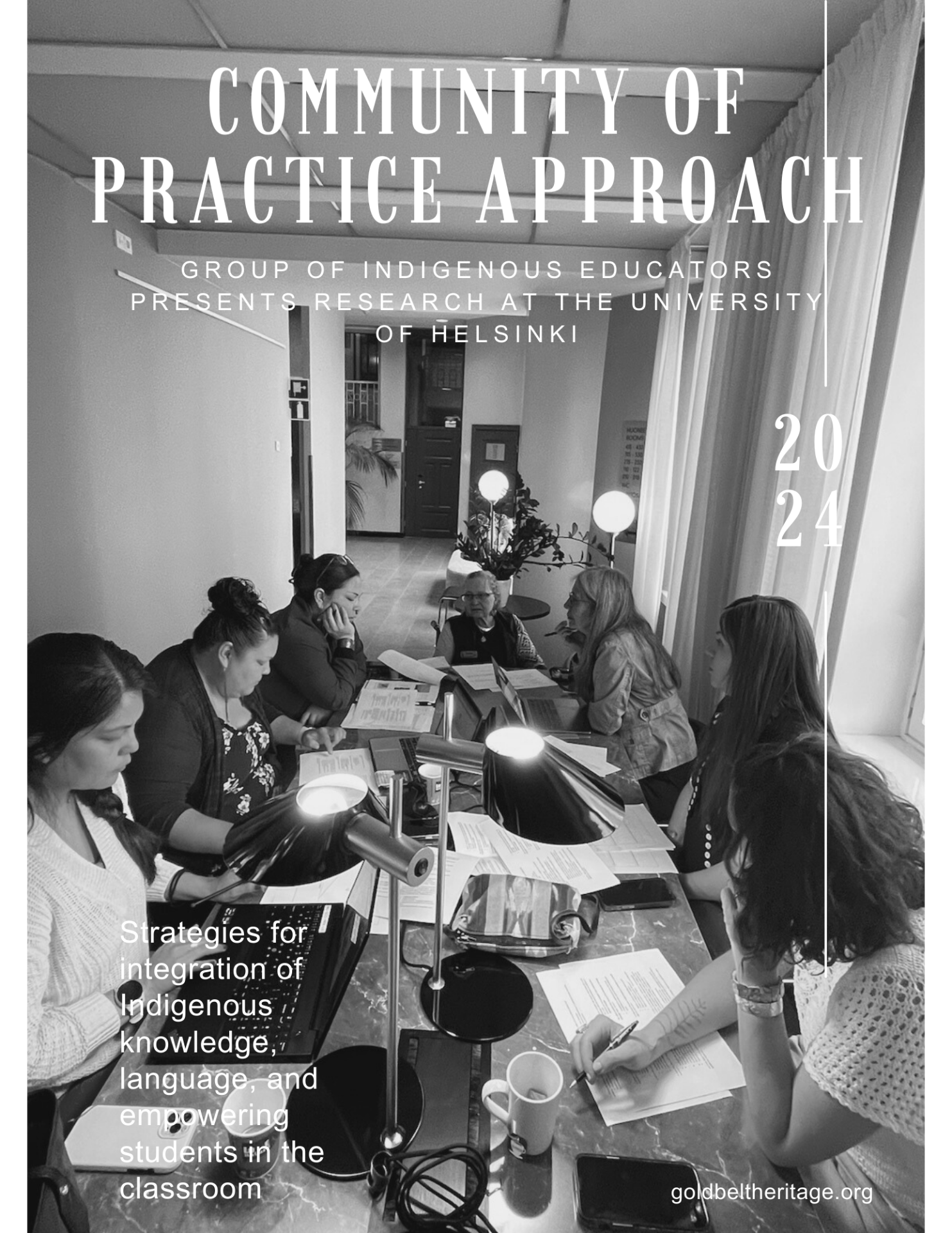

GROUP OF INDIGENOUS SOUTHEAST ALASKA EDUCATORS PRESENT COMMUNITY OF PRACTICE MODEL AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI

Through funding provided by the Goldbelt Heritage Foundation and based on a Sealaska Heritage Institute Community of Practice approach, a group of Southeast Alaska educators recently traveled to the Reimagining Teachers and Teacher Education for Our Futures conference at the University of Helsinki in Finland. They presented findings for a Community of Practice approach to strengthening educational practices that makes Indigenous language and pedagogies a central component to the classroom.

Organized and funded by Sealaska Heritage Institute as a component of the Indigenizing Education for Alaska program, the Indigenous Educator’s Community of Practice started meeting in the fall of 2023. Indigenous teachers were recruited from across the state, with most educators coming from Southeast Alaska and the Juneau School District. Dr. Angie Lunda was invited to facilitate the group; they met monthly and discussed assigned reading from books and articles pushing back on tokenized “decolonization” and delved into the concept of re-Indigenizing education. As a result of the discussions, the group described four teaching practices that nurture Indigenous students’ cultural identities: 1) using and teaching the local heritage language; 2) contextualizing teaching within a cultural frame, such as an Indigenous cultural story or oral narrative; 3) teaching on and with the Land; and 4) emphasizing cultural values.

In addition to the identification of these four elements, this Indigenous Educators’ Community of Practice (CoP) discussed strategies supporting student well-being and cultural awareness in the classroom. Several in the CoP also described a need to strengthen resolve and empower one-another. Education challenges for teachers have increased because of new laws such as the Alaska Reads Act, classroom time allotted to standardized testing, and a de-emphasis on cultural learning and design.

THE COP GAVE US A SAFE PLACE TO SHARE WHO WE ARE AND HOW WE BECAME EDUCATORS. IT GAVE US A SAFE PLACE TO SHARE WHY WE’RE SO MOTIVATED IN REIMAGINING THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM WITHIN OUR REGION. – CHELSEE COOK

Many people in the group wanted to uniquely push back on the time and implementation restraints around classroom learning design that come with the Alaska Reads Act. While all in the CoP agreed that reading is important for all students, so is maintaining a balance for students’ social and emotional well-being and ability to make connections to their own world.

According to Amber Frommherz, CoP member, the unique magic of the CoP was founded in “fellowship and edification.” Participants explored a longing to reclaim Indigenous culture and systems of pedagogy. Some of the most uplifting moments emerged from conversations within the CoP that illuminated the depth of indigenous-based methods and classroom design already being used.

Teachers frequently selected examples of student work, filmed their own teaching, or provided reflection based on their implementation. Each teacher then commented on others’ work and were encouraged to try similar practices within their own classrooms. They were also challenged to locate microvalidations where teachers reinforced students’ knowledge and belonging, a term coined by Dr. Angie Lunda.

Shawna Puustinen, teacher and CoP member, explained that as the team met both in person and via zoom, the content and discussion was furthered by who was in the room. According to Puustinen, surrounding ourselves with other Indigenous educators and with such a powerful group of people the team grew together quickly. “The team evolved based on our own journeys and the structure of the group.“ We were successful in trying new ideas and content and supported by our peers when something did not go to plan. While meeting on nights and weekends was difficult, Puustinen said that there were many things to look forward to, and the group helped to rejuvenate and strengthen our own practice. In addition, articles selected by the group leader, Dr. Angie Lunda, helped ground the conversations.

The group was not without struggle, noting that it was difficult to find time in the teachers‘ already busy schedule, but because of the camaraderie and fellowship, teachers continued to pursue their learning. Dr. Lunda was noted by multiple participants being the key ingredient to the success of the group. She frequently met teachers where they were at in terms of time and participation and worked with teachers individually to support trying new design techniques and practices in their classrooms. Many teachers were unaware that they were already embedding and utilizing Indigenous methodologies intuitively in their regular classroom routines.

Throughout the year, Dr. Lunda began observing themes and commonalities in the reflections and teaching videos shared by participants. Based on analysis of the data, the team discerned and described successful practices that can be implemented in every classroom and rooted in cultural identity, language, and Indigenous methodology.

The team was excited when their abstract was selected to present findings at the prestigious Reimagining Teachers and Teacher Education for Our Futures conference at the University of Helsinki in Finland. In connection with the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the University of Helsinki welcomes visitors from across the globe to discuss “the crucial role that teachers have in shaping the critical, transversal skills that are necessary for our futures” (Conference Website).

Through funding provided by Goldbelt Heritage Foundation, a small cohort was able to attend this conference to present findings from the CoP. During a 90-minute panel discussion, members of the CoP discussed the scope of the yearlong work and how it enhanced their classroom through the use of heritage language, supporting student identity, and reinforcing the group’s innate perspectives as Indigenous educators. Specifically, the CoP model created a space where teachers could support each others’ ideas and identities and deconstruct historical assumptions surrounding classroom learning.

While the session was limited to 90-minutes, educators from around the world stayed much longer to talk with the panelists and to continue conversations that started during their presentation.

As a result of the presentation and research, the panelists were invited to contribute to articles and even a chapter in a book re-establishing the important role of building classrooms through heritage language and Indigenous pedagogies.

I HEARD PEOPLE FROM AFRICA, SYRIA, FINLAND, AND CANADA, TO NAME A FEW, SHARE ABOUT THE NEED TO PRESERVE AND USE INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES, STORIES, AND WAY OF LIFE AS A WAY TO SUPPORT AND UPLIFT ALL STUDENTS- BARBARA DUDE

Other highlights from the conference included exchanges of ideas with other presenters, learning about trends and themes in education from other parts of the world, broadening access to Indigenous perspectives through classroom education, and encouragement that supports re Indigenizing education and promoting heritage language.

The Community of Practice approach was seen as an important and innovative method to support teachers and the students they serve.

IMPORTANT LINKS:

For curriculum and educational resources, please visit our Haa Shuká Tundatáani site:

For additional information on the article or to be placed in touch with CoP members, please email: luke.fortier@goldbelt.com Education Coordinator at Goldbelt Heritage Foundation

For further information about joining next years CoP, scan the QR code for Sealaska Heritage Institute’s main website, or email Adriana Northcutt at iea@sealaska.com

The Indigenizing Educator’s Community of Practice is offered by Sealaska Heritage Institute and funded by US DOE ANEP Grant PR#S356A210026. Contents of this article do not necessarily represent the policy of the DOE and should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Comments